Thirty-seven years ago, a horrific incident unfolded in Rajasthan, India, that shocked the nation and the world. A young widow named Roop Kanwar was burned alive on her husband’s funeral pyre in a brutal act of sati—a centuries-old Hindu practice where widows were expected to self-immolate. This tragedy marked the last widely known case of sati in India, and it spurred a legal and social movement against the practice. However, recent developments in the case have reignited the debate and sparked outrage over the acquittal of the remaining accused.

A Tragic Death That Shocked the World

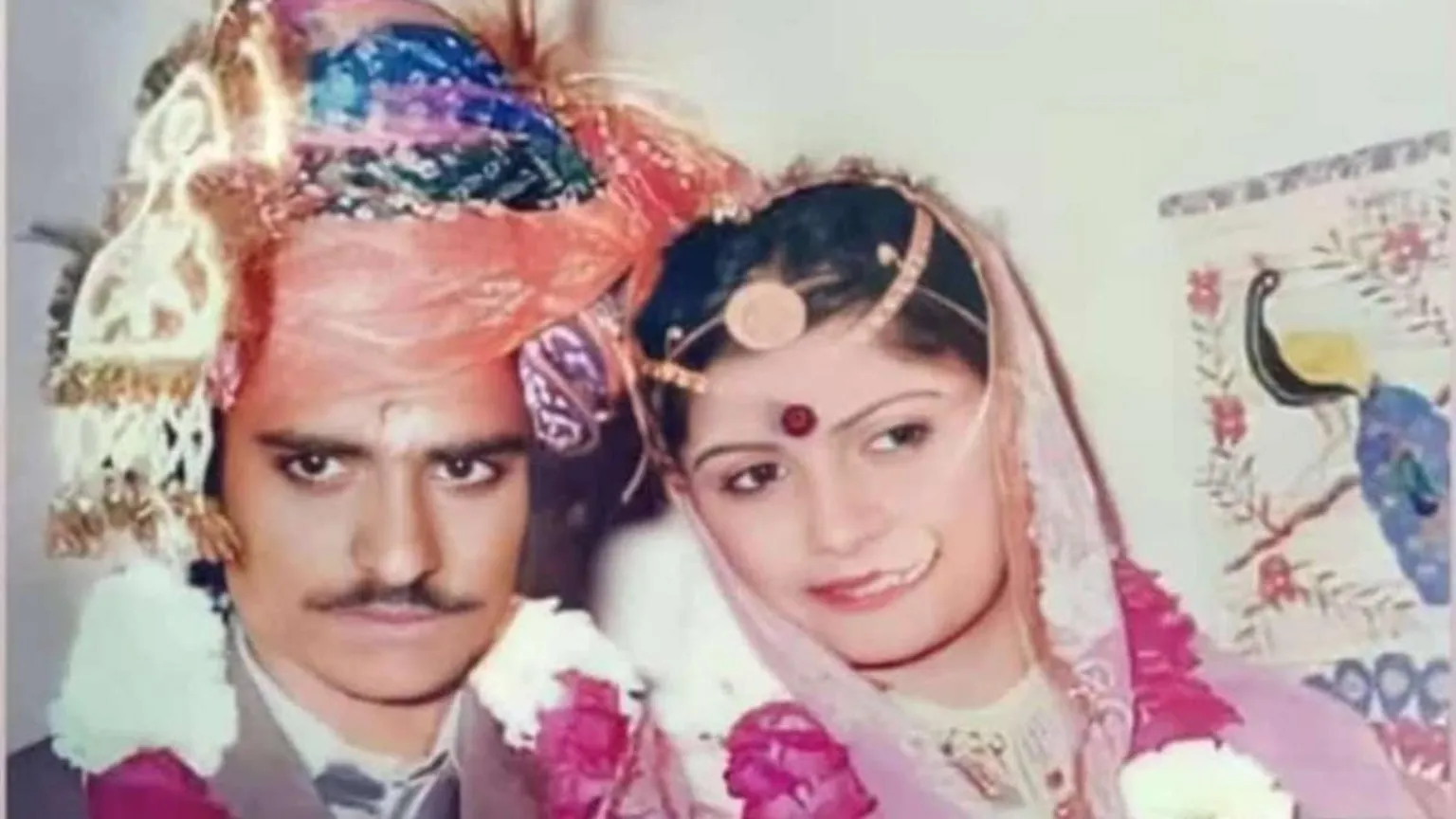

On September 4, 1987, in the village of Deorala, Roop Kanwar, an 18-year-old widow, was allegedly forced onto her husband’s funeral pyre, where she burned to death. Witnesses claimed the event was a public spectacle, watched by hundreds of villagers, many of whom glorified the act as a demonstration of bravery and devotion. Kanwar’s death was a catalyst for protests and widespread condemnation, leading to the introduction of the Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987, which outlawed the practice and its glorification.

The law imposed severe penalties for anyone involved in committing or promoting sati, including the possibility of life imprisonment or death. However, despite the initial outcry and the enactment of the law, no one has ever been held accountable for Kanwar’s death or the public glorification that followed.

A Shocking Acquittal

In a recent court ruling, eight men accused of glorifying Kanwar’s death were acquitted, marking the end of legal proceedings in the case. The decision has sparked new waves of outrage, especially among women’s rights groups and activists who have long campaigned for justice in this case. Fourteen women’s organizations in Rajasthan have demanded the state government challenge the acquittal in the high court, warning that the ruling could “reinforce a culture of sati glorification.”

Despite widespread public condemnation, including from international human rights organizations, local politicians, and civil society, Roop Kanwar’s death has been romanticized by some sections of society. Her husband’s family and members of their upper-caste Rajput community claim that Kanwar willingly embraced the ritual in accordance with tradition, despite reports suggesting otherwise.

A Question of Voluntariness

Kanwar’s family initially contested the claim that she voluntarily committed sati. They lived just two hours away from Deorala and found out about her death only through news reports the next day. Some eyewitnesses reported that Kanwar had tried to escape from the village and was forcefully dragged to the pyre by villagers. There were also allegations that she had been drugged before being placed on the fire, as witnesses saw her frothing at the mouth and struggling to free herself when the flames rose.

Journalist Geeta Seshu, part of a fact-finding team that visited the village after the incident, documented chilling testimonies of how Kanwar was coerced. “Preparations for the sati began as soon as her husband’s body was brought to the village,” said Seshu. According to her report, Kanwar hid in nearby fields but was discovered and forced back by sword-wielding villagers. “It was nothing but a horrific murder,” Seshu concluded.

A Community’s Power Play

Roop Kanwar’s death was not only a tragedy but also a political tool for the Rajput community, which used the incident to rally support and gain influence. In the aftermath of her death, Deorala became a pilgrimage site, with framed photos of Kanwar being sold and ceremonies held in her honor. Although the Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act banned such glorification, local authorities turned a blind eye to these activities.

Activists have argued that the Indian government and local law enforcement were complicit in the aftermath of the incident, allowing the glorification of sati to continue unchecked. The acquittal of the accused men, many of whom were powerful community leaders, has renewed concerns about the influence of caste politics and the ongoing challenges in bringing justice for Kanwar’s death.

The Path Forward for Justice

Although the practice of sati has been outlawed for nearly two centuries, Roop Kanwar’s case serves as a reminder that the fight for justice is far from over. The acquittal of the last accused men threatens to undermine the progress made in combating the glorification of such barbaric acts. Women’s rights groups and activists continue to push for accountability, calling for the government to appeal the latest ruling and strengthen measures to prevent future glorifications of sati.

While the physical practice of sati has largely been eradicated, its legacy lingers in parts of Indian society. Many believe that allowing Kanwar’s death to go unpunished sends a dangerous message that such acts can be celebrated without consequence. For them, the case represents not just a legal battle but a broader fight against the normalization of violence against women in the name of tradition.

A Symbol of Resistance

Roop Kanwar’s death was supposed to be the end of a horrific practice, but 37 years later, her case still resonates with a society grappling with the balance between tradition and justice. As activists continue their fight for accountability, Kanwar has become a symbol of both the struggle for women’s rights and the dangers of political manipulation in India.

The acquittals in the case may have closed one chapter of the legal proceedings, but for many, the fight for justice in the last known sati case is far from over. As Roop Kanwar’s story returns to the headlines, it raises a critical question: Will India ever truly reckon with the dark legacy of sati, or will it continue to glorify the past at the expense of progress?